This a review of the Iron-Clad Java: Building Secure Web Applications book.

(My) Conclusion

I will start with the conclusion because it’s maybe the most important part of this review.

For me this is a must read book if you want to write more robust (web and non web) applications in Java, it covers a very large panel of topics from the basics of securing a web application using HTTP/S response headers to handling the encryption of sensitive informations in the right way.

Chapter 1: Web Application Security Basics

This chapter is an introduction to the security of web application and it can be split in 2 different types of items.

The first type of items is what I would call “low-hanging fruits” or how you could improve the security of your application with a very small effort:

- The use of HTTP/S POST request method is advised over the use of HTTP/S GET. In the case of POST the parameters are embedded in the request body, so the parameters are not stored and visible in the browser history and if used over HTTPS are opaques to a possible attacker.

- The use of the HTTP/S response headers:

- Cache-Control – directive that instructs the browser how should cache the data.

- Strict-Transport-Security – response header that force the browser to alway use the HTTPS protocol. This it can protect against protocol downgrade attacks and cookie hijacking.

- X-Frame-Options – response header that can be used to indicate whether or not a browser should be allowed to render a page in a

<frame>,<iframe>or<object>. Sites can use this to avoid clickjacking attacks, by ensuring that their content is not embedded into other sites. - X-XSS-Protection – response header that can help stop some XSS atacks (this is implemented and recognized only by Microsoft IE products).

The second types of items are more complex topics like the input validation and security controls. For this items the authors just scratch the surface because all of this items will be treated in more details in the future chapters of the book.

Chapter 2: Authentication and Session Management

This chapter is about how a secure authentication feature should work; under the authentication topic is included the login process, session management, password storage and the identity federation.

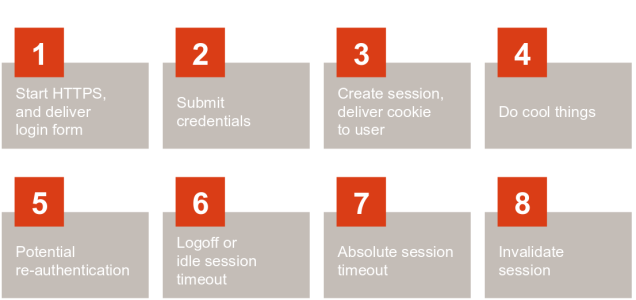

The first part is presenting the general workflow of login and session management (see next picture) and for every step of the workflow some dos and don’t are described.

The second part of the chapter is about common attacks on the authentication and for each kind of attack a solution to mitigated is also presented. This part of the chapter is strongly inspired from the OWASP Session Management Cheat Sheet which is rather normal because one of the authors (Jim Manico) is the project manager of the OWASP Cheat Sheet Series.

If you want to have a quick view of this chapter you can take a look to the presentation Authentication and Session Management done by Jim.

Even if you are not implementing an authentication framework for you application, you could still find good advices that can be applied to other web applications; like the use of the use of the secured and http-only attributes for cookies and the increase of the session ID length.

Chapter 3: Access Control

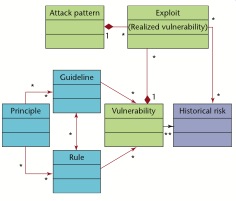

The chapter is about the advantages and pitfalls of implementing an authorization framework and can be split in three parts.

The first part describes the goal of an authorization framework and defines some core terms:

- subject : the service making the request

- subject attributes : the attributes that defines the service making the request.

- group : basic organizational structure

- role : a functional abstraction that uniquely describe system collaborators with similar or unique duties.

- object : data being operating on.

- object attributes : the attributes that defines the type of object being operating on.

- access control rules : decision that need to be made to determine if a subject is allowed to access an object.

- policy enforcement point : the place in code where the access control check is made.

- policy decision point : the engine that takes the subject, subject attributes, object, object attributes and evaluates them to make an access control decision.

- policy administration point : administrative entry in the access control system.

The second part of the chapter describes some access control (positive) patterns and anti-patterns.

Some of the (positive) access control patterns: have a centralized policy enforcement point and policy decision point (not spread through the entire code), all the authorization decisions should be taken on server-side only (never trust the client), the changes in the access control rules should be done dynamically (should not be necessary to recompile or restart/redeploy the application).

For the anti-patterns, some of then are just opposite of the (positive) patterns : hard-coded policy (opposite of “changes in the access control rules should be done dynamically”), adding the access control manually to every endpoint (opposite of have a centralized policy enforcement point and policy decision point)

Others anti-patterns are around the idea of never trusting the client: do not use request data to make access control policy decisions and fail open (the control access framework should cope with wrong or missing parameters coming from the client).

The third part of the chapter is about different approaches (actually two) to implement an access control framework. The most used approach is RBAC (Role Based Access Control) and is implemented by some well knows Java access control frameworks like Apache Shiro and Spring Security. The most important limitation of RBAC is the difficulty of implementing data-specific/contextual access control. The use of ABAC (Attribute Based Access Control) paradigm can solve the data-specific/contextual access control but there are no mature frameworks on the market implementing this.

Chapter 4: Cross-Site Scripting Defense

This chapter is about the most common vulnerability found across the web and have two parts; the presentation of different types of cross-site scripting (XSS) and the way to defend against it.

XSS is a type of attack that consists in including untrusted data into the victim (web) browser. There are three types of XSS:

- reflected XSS (non persistent) – the attacker tampers the HTTP request to submit malicious JavaScript code.

- stored XSS (persistent XSS) – the malicious script is stored on the server hosting the vulnerable web application (usually in the database) and it is served later to other users of the web application when the users are loading the vulnerable page. In this case the victim does not require to take any attacker-initiated action.

- DOM-based XSS – the attack payload is executed as a result of modifying the DOM “environment” in the victim’s browser.

For the defense techniques the big picture is that the input validation and output encoding should fix (almost) all the problems but very often various factors needs to be considered when deciding the defense technique.

Some projects are presented for the input validation (OWASP Java Encoder Project) and output encoding (OWASP HTML Sanitizer, OWSP AntiSamy).

Chapter 5: Cross-Site Request Forgery Defense and Clickjacking

Chapter 6: Protecting Sensitive Data

This chapter is articulated around three topics; how to protect (sensitive) data in transit, how to protect (sensitive) data at rest and the generation of secure random numbers.

How to protect the data in transit

The standard way to protect data in transit is by use of cryptographic protocol Transport Layer Security (TLS). In the case of web applications all the low level details are handled by the web server/application server and by the client browser but if you need a secure communications channel programmatically you can use the Java Secure Sockets Extension (JSSE). The authors recommendations for the cipher suites is to use the JSSE defaults.

Another topic treated by the authors is about the certificate and key management in Java. The notions of trustore and keystore are very well explained and examples about how to use the keytool tool are provided. Last but not least examples about how to manipulate the trustores and keystores programmatically are also provided.

How to protect data at rest

The goal is how to securely store the data but in a reversible way, so the data must be wrapped in protection when is stored and the protection must be unwrapped later when it is used.

For this kind of scenarios, the authors are focusing on Keyczar which is a (open source) framework created by Google Security Team having as goal to make it easier and safer the use cryptography for the developers. The developers should not be able to inadvertently expose key material, use weak key lengths or deprecated algorithms, or improperly use cryptographic modes.

Examples are provided about how to use Keyczar for encryption (symmetric and asymmetric) and for signing purposes.

Generation of secure random numbers

Last topic of the chapter is about the Java support for the generation of secure random numbers like the optimal way of using the java.security.SecureRandom (knowing that the implementation depends on the underlying platform) and the new cryptographic features of Java8 (enhance of the revocation certificate checking, TLS Server name indication extension).

Chapter 7: SQL Injection and other injection attacks

This chapter is dedicated to the injections attacks; the sql injection being treated in more details that the other types of injection.

SQL injection

The sql injection mechanism and the usual defenses are very well explained. What is interesting is that the authors are proposing solutions to limit the impact of SQL injections when the “classical” solution of query parametrization cannot be applied (in the case of legacy applications for example): the use of input validation, the use of database permissions and the verification of the number of results.

Other types of injections

XML injection, JSON-Based injection and command injection are very briefly presented and the main takeaways are the following ones:

- use a safe parser (like JSON.parse) when parsing untrusted JSON

- when received untrusted XML, an XML schema should be applied to ensure proper XML structure.

- when XML query language (XPath) is intermixed with untrusted data, query parametrization or encoding is necessary.

Chapter 8: Safe File Upload and File I/O

The chapter speaks about how to safety treat files coming from external sources and to protect against attacks like file path injection, null byte injection, quota overloaded Dos.

The main takeaways are the following ones: validate the filenames (reject filenames containing dangerous characters like “/” or “\”), setting a per-user upload quota, save the file to a non-accessible directory, create a filename reference map to link the actual file name to a machine generated name and use this generated file name.

Chapter 9: Logging, Error Handling and Intrusion Detection

Logging

What should be be logged: what happened, who did it, when it happened, what data have been modified, and what should not be logged: sensitive information like sessions IDs, personal informations.

Some logging frameworks for security are presented like OWASP ESAPI Logging and Logback. If you are interested in more details about the security logging you can check OWASP Logging Cheat Sheet.

Error Handling

On the error handling the main idea is to not leak to the external world stacktraces that could give valuable information about your application/infrastructure to an attacker. It is possible to prevent this by registering to the application level static pages for each type of error code or by exception type.

Intrusion Detection

The last part of the chapter is about techniques to help monitor end detect and defend against different types of attacks. Besides the “craft yourself” solutions, the authors also re presenting the OWASP AppSensor application.

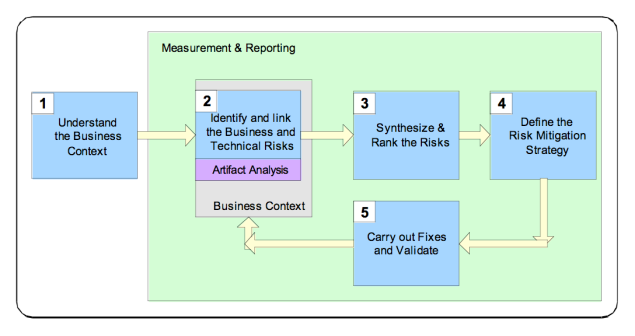

Chapter 10: Secure Software Development Lifecycle

The last chapter is about the SSDLC (Secure Software Development Life Cycle) and how the security could be included in each steps of development cycle. For me this chapter is not the best one but if you are interested about this topic I highly recommend the Software Security: Building Security in book (you can read my own review of the book here, here and here).

You must be logged in to post a comment.